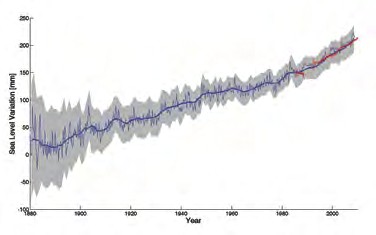

figure 6. Observations show that

the global average sea level has

risen by about 20 cm (8 inches)

since the late 19th century. Sea level

is rising faster in recent decades;

measurements from tide gauges

(blue) and satellites (red) indicate

that the best estimate for the

average sea level rise over the last

two decades is centred on 3.2 mm

per year (0.12 inches per year). The

shaded area represents the sea level

uncertainty, which has decreased as

the number of gauge sites used in

the global averages and the number

of data points have increased.

Source: Shum and Kuo (2011) | Long-term measurements of tide gauges and recent satellite data show that global sea

level is rising, with best estimates of the global-average rise over the last two decades

centred on 3.2 mm per year (0.12 inches per year). The overall observed rise since 1901 is

about 20 cm (8 inches) This sea-level rise has been driven by (in order of importance): expansion of water volume as the ocean

warms, melting of mountain glaciers in most regions of the world, and losses from the Greenland and

Antarctic ice sheets. All of these result from a warming climate. Fluctuations in sea level also occur due to

changes in the amounts of water stored on land. The amount of sea level change experienced at any given

location also depends on a variety of other factors, including whether regional geological processes and

rebound of the land weighted down by previous ice sheets are causing the land itself to rise or sink, and

whether changes in winds and currents are piling ocean water against some coasts or moving water away.

The effects of rising sea level are felt most acutely in the increased frequency and intensity of occasional

storm surges. If CO2 and other greenhouse gases continue to increase on their current trajectories, it is

projected that sea level may rise by a further 0.5 to 1 m (1.5 to 3 feet) by 2100. But rising sea levels will

not stop in 2100; sea levels will be much higher in the following centuries as the sea continues to take up

heat and glaciers continue to retreat. It remains difficult to predict the details of how the Greenland and

Antarctic Ice Sheets will respond to continued warming, but it is thought that Greenland and perhaps West

Antarctica will continue to lose mass, whereas the colder parts of Antarctica could start to gain mass as

they receive more snowfall from warmer air that contains more moisture. Sea level in the last interglacial

(warm) period around 125,000 years ago peaked at probably 5 to 10 m above the present level. During this

period, the polar regions were warmer than they are today. This suggests that, over millennia, long periods

of increased warmth will lead to very significant loss of parts of the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets and

to consequent sea level rise. |